21 Sunday, March 2019:

Marianne David, a senior journalist and Deputy Editor at the DailyFT, one of Sri Lanka’s leading English language newspapers, was helping her domestic aid put together a feast for Easter lunch. Having started early, they were nearly done by 8:00am—when David decided to quickly scroll through Twitter once again, as was customary for her. One tweet jumped out—it mentioned ‘something’ had happened in Negombo. David switched to her work WhatsApp group, and fragments of updates started coming in: a disturbance at the Kingsbury, possibly a gas leak. More fragmented bits of news started filtering in of simultaneous explosions around the country.

It was almost exactly ten years since explosions last rocked the nation.

Last Easter, a relatively unheard of Islamist organisation, the National Thawheed Jamath (NTJ) launched a series of attacks inspired by the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) targeting three churches, and three hotels; killing 269 people and injuring over 400. Among the dead were at least 45 children, and 40 foreigners. The Parliamentary Select Committee (PSC), appointed to look into the terrorist attacks, noted that the State Intelligence Service Chief, Nilantha Jayawardena, was primarily responsible for not taking adequate action based on intelligence he received regarding growing Islamist extremism in the country.

The report submitted by the PSC also noted that information about armed extremists in Kattankudy was made public as early as 2011, and that the Sri Lanka Thawheed Jamath (SLTJ) came under the Terrorist Investigation Department’s (TID) radar around 2013-2014. Precisely one year since the attacks, the government is still ‘investigating’ how it occurred.

Fresh arrests have been made, including that of prominent lawyer Hejaaz Hizbullah – the latter, since then has been greatly contested due to the lack of remand order. On 15 April, Police Spokesperson Jaliya Senaratne revealed that a total of 197 suspects, including supporters of the NTJ, have been arrested. He also claimed that a second attack was planned following the Easter Sunday carnage. No further details about the arrest of Hizbullah, or of the alleged plot, have been revealed as of this update.

On a Saturday in March 2020, a few weeks short of a year since the attacks, we are in a bus, on our way to St. Sebastian’s Church in Negombo. St. Sebastian’s was the first to be targeted last year, the one which sent waves of shock and panic through the nation; one which also filled you with fear for loved ones you knew who would be there. Then we heard of the explosion at St. Anthony’s in Kochikade — one of the more popular churches in Colombo, widely believed to have miraculous properties, and one that welcomed people of all faiths.

But that was last year. This year, we are on our way to Church on a balmy Saturday morning, wondering how much would have changed in a year. We are pensive and quiet, and the three-wheeler who takes our hire from the Katuwapitiya Junction doesn’t make idle chatter or ask questions. He charges Rs. 80.

The church is uncannily quiet and calm. There are a few devotees inside, spread across the pews, far apart.

Heads bowed in prayer, no one raises their heads as we walk in. The first indication anyone would get of something horrific even happening here is of the military checking identity cards at the church entrance. Walking across the immaculate lawn and the freshly painted building, it is almost impossible to believe that this sanctuary was terrorised.

Middle-aged devotees, trailed by young children, hand out freshly-baked buns, kiribath and bananas to visitors. Cats lounge in the courtyard and mynahs have a tussle out at the back. However, there are reminders of last year in place: the blood-splattered, shrapnel-damaged statue of the Risen Christ in its glass casing; damaged tiling with pyrex over it, possibly where the terrorist detonated the bomb; the wooden noticeboard on the outside, with photos of the repercussions.

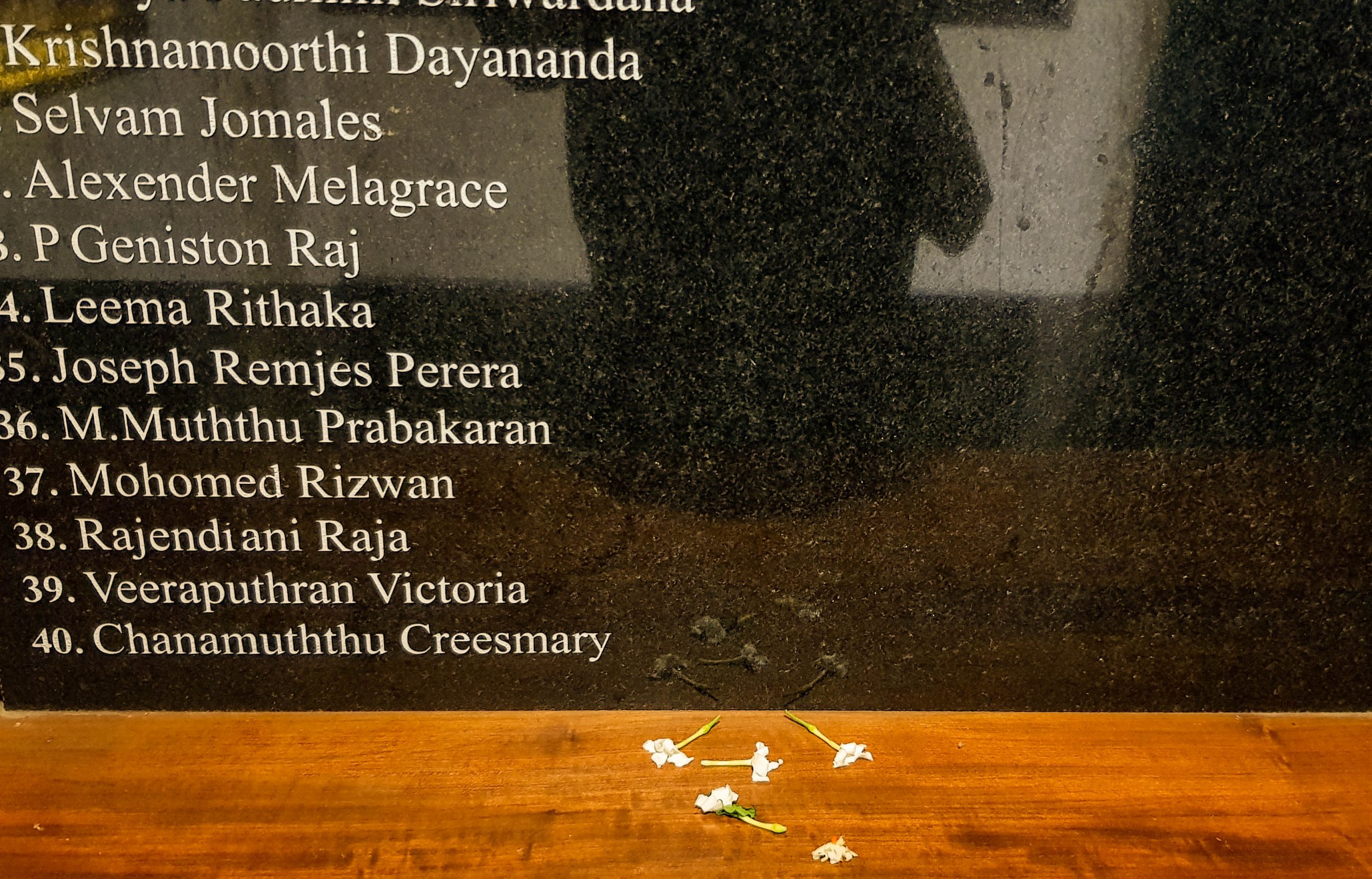

In contrast, St. Anthony’s Shrine in Kotahena, an hour away, is still thrumming with activity. While the main section of the church is fully reconstructed, there is still a lot more going on outside, and around the edges. You have military presence, and you have construction workers, lorries, and a haze of dust. Just outside the entrance is a side-room of sorts – a memorial for the 55 devotees who were killed in the bombs. A plaque lists the names of those who are identified, with a bit of space left at the bottom. In between numbers 36 and 38 (M. Muthu Prabakaran and Rajendianni Raja) is a rather unexpected name — Mohomad Rizwan, a fifteen-year-old Muslim who was at Church on Easter Sunday.

Mohomad Yaseen Rizwan and his aunt, Rajendra Radha, were two of the many casualties of the Easter Sunday attack. The day of the incident, Yaseen’s parents recalled, were like any other.

Yaseen’s father, Rizwan, is a three-wheeler driver. It was during one of his trips he received the news of the attack on Kochchikade. He didn’t believe it at first.

“…but then there were two policemen who wanted to go to Kochchikade. I asked them if the news was true, when they said it was. I quickly called my wife and we both went to the church,” he said.

With a Muslim father and a Hindu-Christian mother, Yaseen fasted during Ramadan and went for the congretational Jummah prayers at the mosque every Friday afternoon. Together with his aunt, he would also visit the Kochikade shrine during Christian holidays, and worship at temples and kovils in the same breath.

Growing up, Yaseen was mostly around his grandmother, Sellamma. She tells us how their entire family went to a temple in Kurunagala just the day before Easter.

“When we heard of the explosion, I was sure he was not dead. He has not harmed anyone in his life; he was innocent and he practiced his religion. I thought he survived and I thought he would come home. But he didn’t. We found his body at the hospital.”

Rizwan and his wife Manju spent the entire day searching for Yaseen and his aunt, but were unable to find them. It would be on the next day that they would see them at the hospital morgue.

Reconstruction in the Zion Church seems to be a lot slower; almost at a halt. Most of the world seems to have moved on, except, of course, those affected directly.

“When we sat down for breakfast that day, there was no public alert of an attack,” Dhulshini de Soyza, mother of Kieran, an eleven-year-old who lost his life in the bomb, told the BBC in Terror in Paradise, the documentary outlining the series of state negligence, and rising radicalisation, that led to the attacks. “If we had received one, we wouldn’t have gone there for breakfast. I wouldn’t be sitting here with you. Keiran would still be here.”

For Marianne David, a seasoned journalist who reported on the civil war, the Easter bombings were by far one of the worst she had experienced, purely because of how unexpected it was.

Slipping back into old routines, David distinctly remembers getting into her deck shoes, and of flashbacks to the 2008 Dambulla bus bombing, before running out to the national hospital.

“It’s something I had always done before because you never know what you’re going to be stepping in when there’s been an explosion.” This time around though, she was also leaving her daughter back at home, a young girl who saw what happened on TV and asked why her mother had to leave.

“If I didn’t go, how can I ask anyone else to? It’s work. You just go out, and… you do your job.”

One year later, it still haunts her.

One year later, there is still no justice.

One year later, the Cardinal says he forgives the Easter bombers.

But there is still no justice.

And elections are around the corner.

Story by Aisha Nazim

Photos by Aisha Nazim and Zahara Dawoodbhoy