Like many teachers around the world experiencing the sudden shifts in formal education caused by school closures, I have had to readjust. This readjustment has included recalibrating teaching methods, reassessing priorities with subject material, and repositioning students’ learning outcomes.

Initially, although communicating with students via email, I was intent on maintaining the momentum of the classroom, constantly reminding myself that within a couple of years these students would be sitting for a graded exam. I was concerned by the lack of interaction involved in our email exchanges because the subject I teach–one called Global Perspectives and Research–requires students to engage with course material, in large part, through discussion and debate.

When the school’s administrators scheduled classes online, I was pleased by the prospect of having discussions in real-time but was also faced with a new challenge. Although the school is a reputed one, and considered one of high prestige, not all students come from equally privileged backgrounds. A few students expressed that it would be difficult for them to participate consistently as they either rely on their parents’ Wi-Fi hotspots to access the internet (a situation that becomes difficult when the parent is unable to lend the student their device) or because they do not possess the adequate data quotas. Although the school was quick to take these situations into consideration and make alternative arrangements, the students, parents, and teachers spoken to for this article provided a range of accounts—of successes and difficulties—in sustaining formal education during this time.

The COVID-19 crisis has caused ruptures in systems of education worldwide, revealing existent inequalities in access to services and raising questions about the effectiveness of virtual education. Online platforms have rapidly been made use of in a range of education institutions across the globe in an attempt to ensure that classes continue in as normal a fashion as they otherwise would. However, the necessity of moving education exclusively to online platforms has highlighted global, regional, national, and also more localised disparities, for not everybody is equipped with the hardware, the software, or—in some cases—the conducive environment required to effectively participate.

With issues regarding the digital divide becoming more pronounced during this crisis period, Fire Escape reached out to students, parents, and teachers from some state, private, and international education institutions across Colombo to understand the range of experiences they were having in sustaining formal education since schools closed in mid-March.

Lack of Access to Digital Technologies

18-year old Shihara*, an A-level student at a private school whose teachers have been sending her and her younger sister weekly worksheets via email, has had difficulty accessing a device through which to check her email since her school closed. Recently, Shihara’s older sister lent them her phone, which finally provided them access. Expected to complete this work in her writing book and submit it to her teachers once school reopens, Shihara expressed frustration at not having been able to access email for the past few weeks because, “now it’s stressful to try to catch up.”

In many middle/lower-middle income households, a single device may be shared by all members of the household, which can make it difficult for students to access, and consistently submit, homework via online platforms. Another issue, aside from lacking hardware, is that of limited data, which could be due to unaffordable costs or because children are “left to their own devices” and may use data for other purposes.

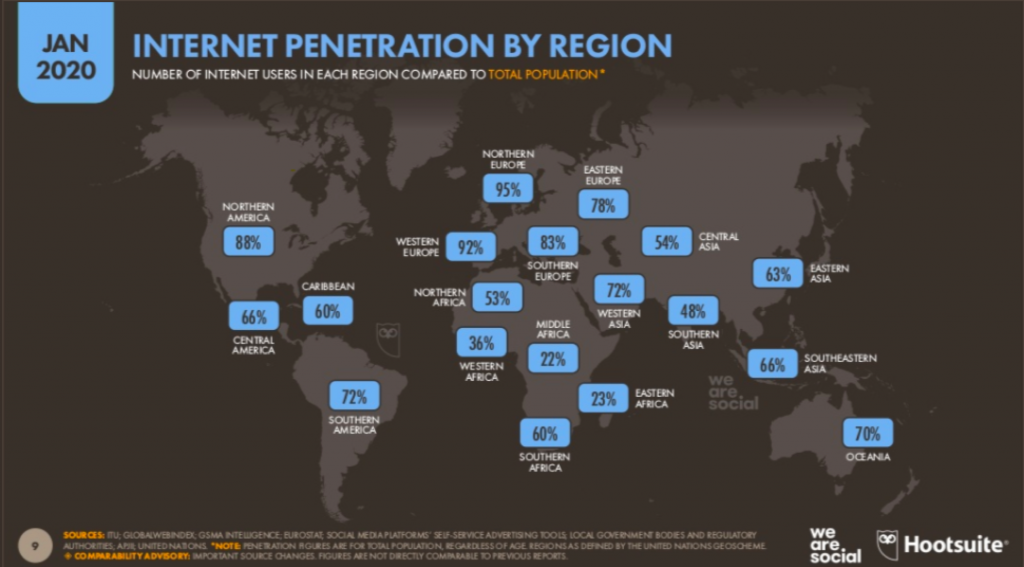

Photo Credit: Datareportal

A Halt to Exams & No Job Prospects in Sight

Confronting a threatening pandemic and its expected consequences, education institutions and exam boards around the world have been forced to take necessary action, rescheduling exams or introducing alternative methods of assessment.

Thilini*, a third-year student enrolled in a Bachelor of Arts program at a state university, was preparing for her final exams when the COVID-19 crisis in Sri Lanka began intensifying. The first COVID-19 positive patient was detected on March 11, and when her university closed on March 13, the count had risen to three.

Since then, she has been receiving e-books and articles—tonnes, she emphasises—as email attachments. “We were told that we would begin classes through an e-learning system but nothing has happened so far. We just function through email and [by] checking the university’s websites for updates that lecturers post there.”

Some of her classmates in the General program who were due to graduate this May appear to be struggling with the disruption that this has caused.

Senali* was due to complete her program following exams that were set for March 14. Due to the fact that she was unable to sit for her final exams, she has not received a final grade and has not been able to request a final transcript. Although not having an up-to-date transcript is worrying, “there don’t seem to be any work options at this time anyway” she commented. Senali explained that she has sent her CV to two companies that were advertising positions—she has yet to receive a response.

With 81% of the global workforce having had their workplaces partially or fully closed, and tens of millions facing job loss as the crisis escalates, the International Monetary Fund warns that this could be the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression.

Continuing with Exams/ Alternative Methods of Assessment

Some institutions, on the other hand, are continuing with their pre-crisis exam schedule. Jason*, in his third-year of an Engineering program at a private university, described how although many of his exam modules have been postponed, his university is moving forward with a few of them. “Next week, I have an online exam. The paper will be two hours long and we will have an extra two hours to upload scans of the work done manually.”

He is also expected to submit two lab reports online via a portal. Throughout this period, he has had access to e-lectures that have been uploaded by the foreign university that will ultimately be awarding him his degree. Lecture slides and tutorials can be viewed and downloaded from the internet, and if he has questions or issues, he can request his lecturers’ help through a scheduled Zoom meeting.

Roshana*, a Grade 12 student at an international school, talked about how, with the international exam board that her school follows having cancelled exams worldwide, “it’s been pretty scary for the older students, since our futures depend a lot on these grades.” She explained how even though exams are cancelled, students will likely be assigned a final grade based on classwork. This worries her because it is work that she “didn’t think would ever impact her final grade” and so work into which she didn’t put as much effort.

“There’s also talk that we might have to re-sit the entire year” she said. “Right now, we don’t know what’ll happen.”

That some institutions are continuing with their exam schedules while others are following alternative methods of assessment highlights the difficult decisions that education institutions have had to make. Unable to follow uniform guidelines, the range of solutions indicate inconsistencies that some may believe unfair, and others may believe an expected resolution to this unprecedented situation.

Lack of Contact Between Students and Teachers

Acknowledging the growing importance of digital platforms for education in an increasingly globalised, tech-driven world, efforts have been underway in selected areas of Sri Lanka to implement Smart Classrooms. Although this and other similar initiatives are welcome efforts, budget constraints affecting Sri Lankan public schools and limited private-sector participation have been identified as significant challenges to increasing digital technology use in classrooms across the country.

Furthermore, according to the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS), in order for Smart Classrooms to be effective in the Sri Lankan context, other fundamental changes will have to be made to teaching methods and the nature and content of examinations to ensure that these techniques allow the development of desired skills (such as critical thinking and problem solving).

According to the School Census Report of 2017, out of a total 5,643 primary and secondary schools countrywide, 55℅ had computer facilities for students. The Western Province was reported as having the most facilities (with the North Western Province having the least). On the other end, household ownership of a computer or laptop as recorded in 2019 was 22.2% countrywide, with 34.7% of ownership in the Western Province. Sri Lanka’s internet penetration rate stands at 47% and primary and secondary schools with internet connections have been reported to stand at 18%, also concentrated in the Western Province.

The fact that technology-enabled education is limited to better-resourced areas and education institutions means that many students without such access have had little to no contact with their teachers thus far.

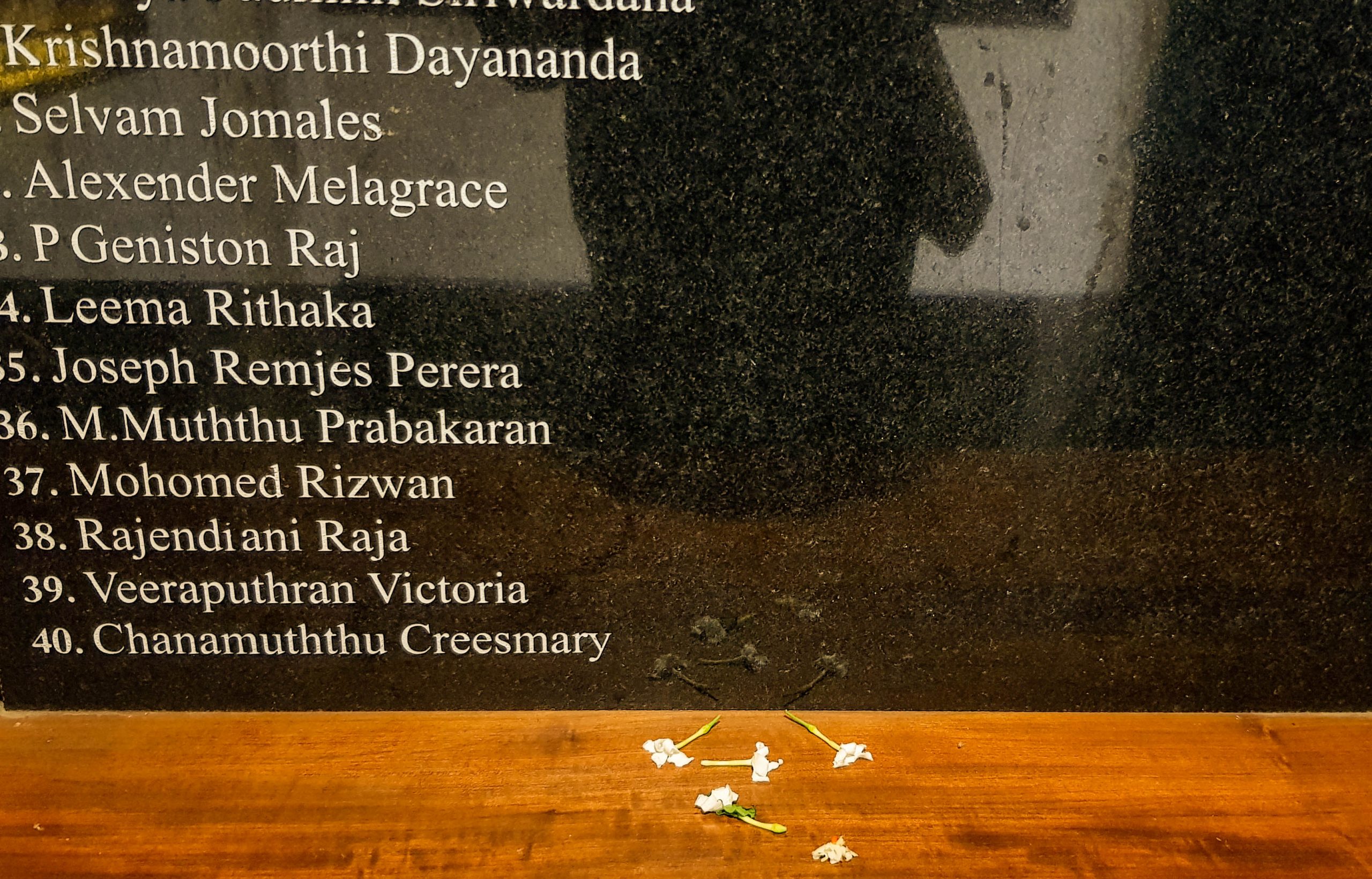

Photo Credit: India Today

Niluka*, whose 11-year old daughter and 13-year old son attend a state school, noted that school closures have been felt differently by each of her children.

Her son was given one practice paper before his school closed, and since then his teacher has uploaded some work onto YouTube and sent some work through WhatsApp. “It is not enough – he has already finished the work he was given.” Her daughter on the other hand was given a larger quantity of worksheets and questions to complete, so she has had relatively more school work to keep her occupied.

Shashi*, whose 13 and 8-year old daughters attend a Tamil-language state school, expressed similar concerns. “My daughter received homework through a WhatsApp message but she has already completed it and now has nothing to do.”

Her children are studying with the limited subject materials at their disposal, and while fearful of the wider harmful impacts of the crisis, she is anxious that her children resume their school routines.

Adverse Effects on Mental Health

The stress and anxiety experienced by parents, students, and teachers alike to ensure that students do not fall behind academically has dramatically risen during this period. This is important to consider, on top of the general anxiety and stress caused by the pandemic, when thinking about the position and role of schools, teachers, parents, and teaching strategies during this time.

Ms. M*—a teacher of English Literature—feels that it is important that the private school she teaches at attempts to incorporate meditation, special prayer times, or activities that are “more creative and fun” into schedules, instead of focusing solely on academics. “These are times of stress so these kinds of activities would be good for the children.” She also expressed that having to schedule online classes and dedicate a number of hours per week to them, while attending to ordering groceries, running the household, and taking care of family matters, has put a strain on her.

She shared a message to a group chat with her colleagues on WhatsApp, which emphasised that during this time, “it’s important not [to] reimpose the rat race on ourselves, students and parents.” Aware of the pressure that students are often put under to perform well, and acknowledging the universal stress caused by this crisis, she commented that, “lockdown has taught us to learn to enjoy slowing down, being creative, having quality time with family, and valuing nature. Learning will help students have somewhat of a routine and focus but it should be a joy not a chore.”

Photo Credit: Mymindourhumanity Campaign

Well-Prepared & Digitally Fluent

The mother of 13-year old Shehan*, who attends an international school, expressed complete satisfaction with the way in which her son’s education has continued since his school closed on March 12.

“The school was extremely well prepared, and way ahead of the curve,” she told Fire Escape. Shehan’s school held training sessions for all students about navigating Zoom and Google Classroom, and—according to his mother—students were made fully conversant with the lesson format, the work expected of them, and the schedule to be followed. Because students were functioning primarily through online platforms prior to the crisis, adjusting exclusively to an online system was not too challenging.

“The transition for me was painless,” she noted, describing how the school has even scheduled exercise time, “which my son does on his gym mat.”

Roshana described how her school also continues classes through platforms such as Zoom and Google Classroom, and that she has up to three classes a day. “The students (and many of the teachers too) expect this to be temporary, so I don’t feel like they put much effort into things like homework.” She expressed that she prefers this online method to ‘normal’ school because, “there’s less tedious note-taking and we take more advantage of resources online.” She also commented that the classes online can be quite chaotic, with teachers’ video screens often getting disrupted, participants’ background noises becoming distracting, and students often reporting that their microphones ‘suddenly stopped working’ which “probably makes it really exhausting for teachers,” she said.

A Future of Digital Education

The global trend towards technology-facilitated education indicates numerous benefits and an inevitable shift in patterns of teaching and learning. The coronavirus-induced crisis has not only highlighted the necessity of virtual platforms for education, but also the existent inequalities and inequities in access to such platforms. It has also raised questions about the methods, objectives, and priorities of education programs, especially during this time.

The experiences described above were given by students, parents, and teachers in education institutions within Colombo. That schools in the Western Province have the most access to digital technologies, and that such disparities (the extent of which were not explored in this article) exist within a single city, raises broader questions about disparities countrywide. Whereas well-equipped schools have shifted, with relative success, to technology-based methods of teaching and learning, others are lagging behind.

Countries such as Greece and South Africa have been making use of television and radio channels to broadcast educational programs to mass audiences, and although programs such as Rupavahini’s Nena Mihira already broadcast a range of educational content, this could be a feasible path for Sri Lanka to take. The Sri Lanka Rupavahini Corporation’s transmission covers more than 95% of the country, and includes channels in Sinhala and Tamil, which could be one avenue for further investment to ensure a more accessible pathway for children to sustain learning during this period.

What are the best steps for parents and teachers to take during this crisis period while schools remain closed, especially given the lack of indication as to how much longer they’ll remain this way? While considering the longer-term possibilities of digital education, it will be important to consider methods that could be made use of by education institutions—and all those working within and around them—to ensure that children without access to the necessary internet connections and hardware don’t continue falling behind in the way that they have been.

*Names with asterisks have been changed at the request of the interviewees.

Cover image by Zahara Dawoodbhoy